Your C2 infrastructure is only as strong as its weakest architectural choice. Focus often goes to tools and malware on the endpoint, such as the C2 framework, initial access payload delivery method, file format, and shellcode loading technique, like process injection, but the core infrastructure design determines your ability to communicate and stay operational when a defender starts pulling threads.

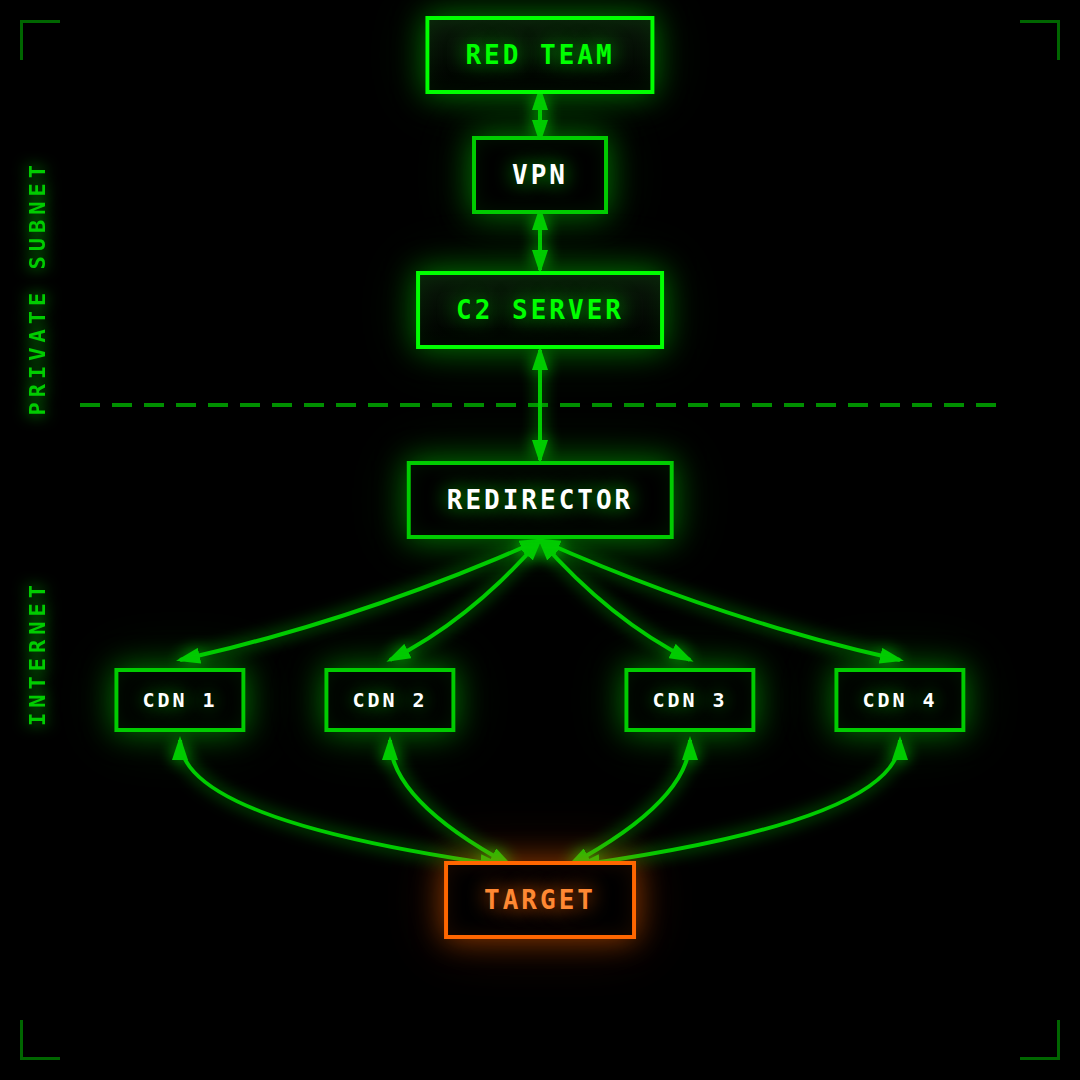

This post explains a layered C2 architecture centered on CDN-based redirection, a centralized redirector and routing layer, trust boundary segmentation, and tunnel-based connectivity. The aim is to create an infrastructure that doesn't fail when a compromise occurs at one layer.

The Architecture at a Glance

The traffic flow looks like this:

Target → CDN Endpoints → Redirector → Reverse Tunnel → C2 Server → VPN → Red Team Operators

Each layer has a specific purpose, and the boundaries between them are intentional. Let's walk through it from the bottom to the top.

The Target-Facing Layer: CDN Endpoints

The implant's callback traffic goes to a well-known CDN provider like Azure CDN, CloudFront, Fastly, or whichever suits the engagement. To a defender reviewing network logs, without anomaly detection such as "is this thing beaconing on a schedule?", this appears as normal outbound traffic to a legitimate CDN—the same kind of traffic generated every second by thousands of real business applications. Blocking an entire CDN IP range is difficult without disrupting half the environment. It's even more effective if you utilize a CDN within the same cloud service provider that the target network relies on.

Why multiple CDNs? Resilience. If a blue team identifies and blocks one domain or CDN endpoint, others remain active. The implant can rotate which one it calls back to, build in fallback logic, and spread traffic across providers so no single one shows a volume spike. You need to understand the rotation logic (round-robin, failover under certain conditions), but these are well-trodden patterns. I've deployed setups with 40 CDN endpoints from 3 different cloud providers, rotated randomly.

Choosing a CDN is more than just about availability. It's important to select providers whose domains are already recognized as legitimate by web proxies and threat intel sources. A callback to d1a2b3c4.cloudfront.net blends seamlessly into enterprise traffic better than a request to a low-cost VPS hosting provider. TLS behavior also plays a role. Some CDNs manage SNI and certificate presentation in ways that allow you to obscure the true origin behind the CDN; others do not.

Researchers at Georgia Tech actually tested 30 CDNs for this in 2023. 22 of them still allowed the SNI/Host header mismatch, including Fastly and Akamai. Cloudfront and Cloudflare had fully mitigated it. Point being, CDN selection isn't just about reputation and availability. You need to understand what each provider's infrastructure actually permits at the TLS layer.

All of these CDN endpoints funnel back to one place: the redirector.

The Redirector: Your Single Chokepoint

The redirector operates behind the CDN layer and its role is to examine incoming requests to determine if they are legitimate C2 traffic or... a curious analyst probing your infrastructure. Actual callbacks are forwarded to the C2 server. All other requests are redirected to a harmless destination, like the company's homepage, a generic 404, or another appropriate page.

This means your C2 server is never directly exposed. The redirector acts as the gatekeeper. It serves as a single chokepoint where you implement your filtering logic once, instead of configuring it across multiple CDNs. This includes user-agent validation, URI pattern matching, header checks, source IP filtering (no need to allow traffic from Asia if the customer you're assessing is in the U.S., and all callbacks originate there, most CDNs support geolocation), and request timing. All of these functions are handled on the redirector, one set of rules, on one device to update whenever you need to make adjustments.

Why One Redirector Behind Multiple CDNs?

You could run one redirector per CDN. But that increases your attack surface, your configuration management efforts, and the number of boxes a defender could potentially fingerprint. A single redirector behind all your CDNs keeps the architecture simple. If you're concerned about it being a single point of failure, that's a valid worry, but it's a problem you address with quick redeployment through automation, not by expanding your infrastructure.

Trust Boundaries: Where the Real Segmentation Lives

This is where the architecture goes from "pretty good" to actually defensible. Think about it in terms of trust boundaries.

Trust Boundary #1: The Internet and the Redirector

The first boundary separates the open internet from the redirector. Everything that arrives here is untrusted: beacon callbacks, scanner traffic, analyst probes. The redirector filters and determines what moves into the next zone.

The redirector is the only component in this setup that has direct exposure to the public internet. It's meant to be replaceable. If a defender finds out and blocks the redirector's IP, you can take it down, deploy a new one, update your CDN origins, and resume. The C2 server, your session data, and your operational history remain unaffected.

This is important: the redirector should be stateless. No logs you can't afford to lose, no configuration that can't be reproduced through automation. Treat it like a disposable filter because that's exactly what it is.

Trust Boundary #2: The Redirector and the C2 Server

The second boundary lies between the redirector and the C2 server, and this is where the architecture needs to become more secure.

The C2 resides in a private subnet with no direct inbound connections. Instead of the redirector forwarding to an open port, the C2 initiates contact with the redirector through a reverse port forward over an encrypted tunnel, such as SSH or WireGuard. This reverses the connection direction, so there is no listening port on the C2 side to detect or probe.

On the redirector, this appears to be a local port bound to the tunnel. When the filtering logic determines a request is a legitimate callback, it forwards the traffic to that local port, which then sends it back through the encrypted connection to the C2 server.

Layer a VPN with strict inbound filtering on top, and even a fully compromised redirector leaves a defender with nowhere to go. They are facing a tunnel endpoint with no route into the C2 subnet.

The only thing exposed to the public internet is the redirector, and the only thing the redirector can access is a reverse-forwarded port linked to the C2 server's tunnel.

The Operator Layer: VPN Access

Red team operators also avoid touching the C2 server over the public internet. Access is via a VPN into the private subnet, completely separate from the callback traffic path.

This separation is important. Operator management traffic (issuing tasks, pulling results, interacting with the C2 console) follows a different path than implant callbacks. If a defender monitors traffic patterns on the redirector, they see callback traffic. They do not see your operator sessions because those don't go through the same infrastructure.

VPN access should be restricted: implement source IP restrictions if your team works from known locations, use certificate-based or key-based authentication, and ideally enforce MFA.

Full Traffic Flow

Trace it end to end:

Callback path: Target implant calls back to a CDN domain → CDN then forwards to the redirector origin → Redirector examines the request → Legitimate traffic is forwarded to the local reverse-forwarded port → Traffic travels through the encrypted tunnel to the C2 server in the private subnet.

Operator path: The operator connects to the private subnet via VPN, authenticates, and then accesses the C2 server directly within the private network.

Analyst/scanner path: Probe hits the CDN domain → CDN forwards the request to the redirector → Redirector inspects the request → Validation fails → Redirects to a benign destination. Dead end.

What a Defender Sees When They Pull the Thread

Let's say a member of the blue team notices suspicious traffic and begins investigating.

Layer 1, CDN: They observe callbacks directed to a legitimate CDN domain. They might flag it or block the domain. If they investigate the CDN, they could find an origin IP. That's the redirector.

Layer 2, Redirector: They target the redirector directly. Since their requests don't match the expected C2 profile, they are redirected to a benign site or a 404 page. The redirector appears as a generic web server. Even if they become aggressive and scan all ports, they locate the tunnel endpoint but cannot traverse it inbound.

Layer 3, C2 Server: They can't access the system. No public IP to locate. No open port to connect to. The only entry point is through the tunnel, which was started from the C2 side. It's a dead end.

This is also why CDN-based infrastructure is hard to triage even at Layer 1. That same Georgia Tech study found that roughly a third of the vulnerable CDNs were also serving known malicious domains. Defenders can't assume CDN traffic is clean just because the provider is legitimate. The infrastructure is shared, and that shared trust is what this architecture exploits.

Failure Scenarios and Resilience

CDN gets burned: Rotate the domain or switch providers. The C2 server remains completely unaffected. Active sessions continue through the remaining CDN endpoints.

Redirector gets burned: Tear it down, then deploy a new one using automation. Update CDN origins to the new redirector IP. The C2 server re-establishes its reverse tunnel. Downtime lasts only minutes if your automation is reliable.

C2 server gets compromised: This is the worst-case scenario, and it's exactly why this architecture exists: to minimize the chances of it happening. The C2 has no public exposure, no inbound ports, and is only accessible through an encrypted tunnel from a disposable redirector and a secured VPN. If someone reaches it, you have bigger problems than just the infrastructure design.

Key Takeaways

The entire architecture is centered on two principles: reducing exposure and ensuring burned components are replaceable.

CDNs enhance your domain reputation and resilience. The redirector provides centralized filtering and a disposable, internet-facing presence. Trust boundaries enforced through reverse tunnels and VPN segmentation ensure that compromising one layer doesn't grant access to the next.

The most valuable part of your infrastructure, the C2 server with all its session data and operational history, is the most protected. Everything in front of it is designed to be destroyed and rebuilt without losing what matters.

Build your infrastructure as if you expect it to get torn apart, because a good blue team will try.

References

Subramani, K., Perdisci, R., & Skafidas, P. (2023). Measuring CDNs Susceptible to Domain Fronting. arXiv:2310.17851. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.17851